Wearables in Healthcare: It’s Time to Decide - by Amir Hadid

By Light-it, in collaboration with Dr. Amir Hadid, Co-founder & CEO @ Sensifai Health | Adj. Prof., Faculty of Medical & Health Sciences, Tel Aviv University

The uncomfortable question

My favorite question to ask a room full of Apple Watch Ultra 2 owners is simple:

“How has your watch made you healthier?”

What follows is almost always the same- an awkward silence, and a glance at the floor. And here’s my unpopular opinion: in many cases, wearables have not improved our health. In some subtle but important ways, they may even have degraded it.

Eighteen years after the launch of Fitbit, and ten years since the first Apple Watch was released, it’s time to face the inconvenient truth: have wearables delivered on their promise to help us live healthier lives, or are they just helping us to monitor our lives in higher definition?

Billions of devices, mixed results

About 40% of Americans now own a wearable device. Globally, the figure is close to one billion. Today’s devices pack astonishing computing power into tiny casings, with multimodal sensors, PPG, accelerometers, and temperature, rivaling research tools from just a decade ago. A fully capable microcomputer lives on our wrist, tracking every step, heartbeat, and breath.

And yet, despite massive adoption, the dream of measurable, widespread health gains from wearables remains largely unfulfilled. While observational studies have found positive correlations between wearable-tracked behaviors and improved health outcomes, rigorous, high-quality randomized controlled trials have not. None have yet to demonstrate improvements in hard clinical endpoints, such as reduced mortality, prevention of hospitalizations, or slowing disease progression.

We need to ask why and what needs to change.

More data ≠ more value

Each year brings new features: from heart rate and steps, to heart rate variability (HRV), temperature, electrodermal activity, and more. The assumption has been that more data would naturally lead to more insights, which would naturally lead to better health. But for most clinicians and users, these huge datasets are overwhelming. They’re not structured around actionable clinical interventions and outcomes, and they rarely fit into existing workflows.

A few weeks ago, during one of my most stressful periods in a year, poor sleep, low energy, elevated resting heart rate, and reduced HRV, my wearable’s AI advisor pinged me with an “insight”:

“We detected a reduction in your resting heart rate over the last six months. It is down by 2 bpm. Your fitness is improving. Well done!”

It was the least relevant feedback I could have received at that moment. Why? Because the model was not trained to understand the context of my current physiological state. It wasn’t built on labeled clinical patterns and/or events, as we see with more acute and well-defined use cases like atrial fibrillation detection. Most wearable insights today are not generated that way, and they remain ignorant of clinical and personal nuance.

Vanity vs. value

When it comes to core metrics like heart rate and HRV, wearables from Apple, Garmin, Oura, and Whoop can now approach near research-grade accuracy. But accuracy without interpretation is an empty promise, so companies create new “insights” to make data digestible.

Take “stress” scores, for example. People act on them as if they were medically validated, but what do these numbers really mean? As an experiment, stir a pot on the stove while listening to your favorite music. You might feel relaxed, but your “stress” score will spike. That’s because the device is not actually measuring stress; it’s estimating it from proxies, and environmental heat alone can skew the reading. Clinically meaningless.

The same goes for the “biological age” trend in the longevity market. Everyone likes hearing they’re younger than their chronological age. Some companies exploit this desire, selling the illusion of youth with limited transparency on how these scores are derived, or whether they mean anything for real-world health. Privileged, motivated people often buy the narrative, but in reality, physiology doesn’t bend to marketing.

Even simple metrics can mislead

If you think energy expenditure would be easy to estimate for a tech company valued at $3 trillion… think again.

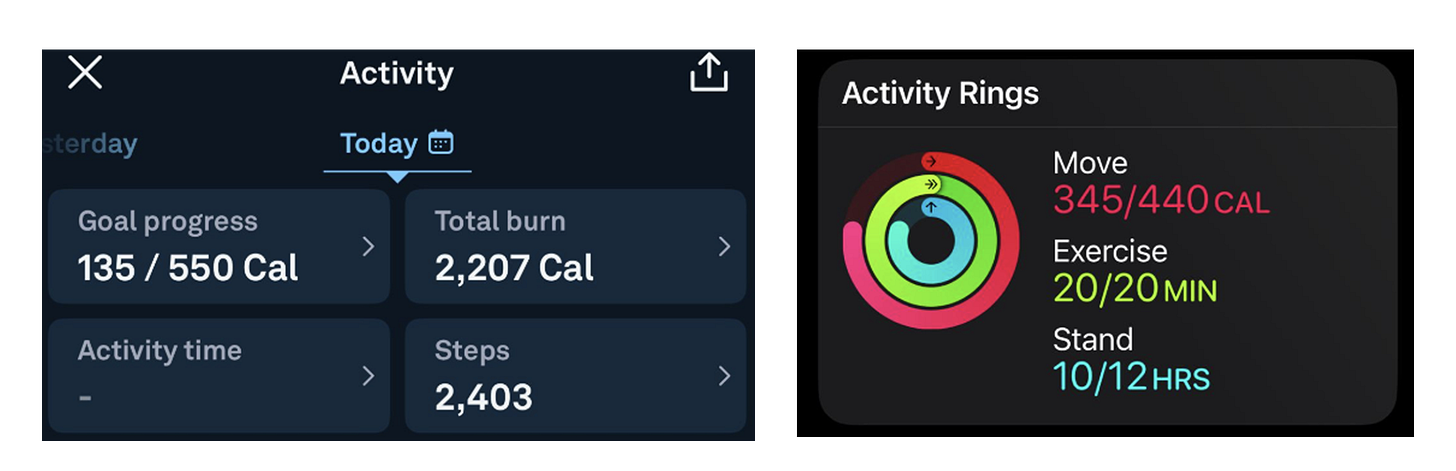

A patient in a prescribed exercise program shared a snapshot from their Apple Watch and Oura Ring after a sedentary day at work (around 6 pm). As can be seen in the figure below, the Apple Watch overestimated their calorie burn substantially, something confirmed by multiple studies.

This isn’t just a rounding error. If people use these numbers to guide diet or weight management, they risk creating an energy imbalance without realizing it. On a behavioral level, “closing the rings” on an Apple Watch after a relatively sedentary day is promoting the opposite of sustained daily activity. In other words, the metric designed to promote movement can inadvertently promote inactivity.

Wearables in Healthcare 2.0

This is not to say wearables can’t be transformative. Atrial fibrillation detection, seizure detection, anaphylaxis alerts, and early asthma or COPD exacerbation detection in people experiencing a chronic disease hold enormous promise. But the path to unlocking this potential requires a shift- from chasing features to building clinically trustworthy systems.

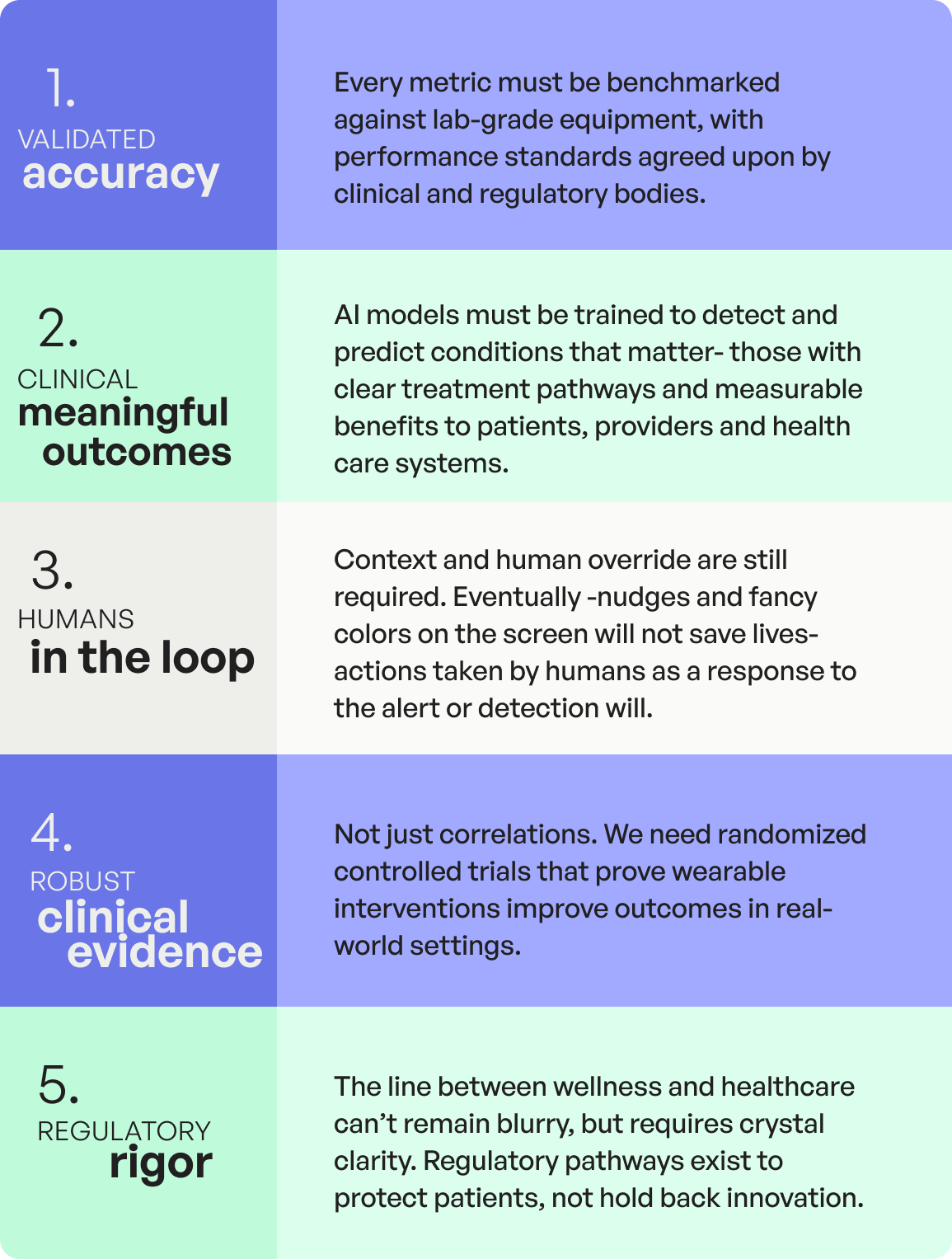

To get there, the industry must commit to five concepts:

The choice ahead

We are at a crossroads. One path keeps wearables in the realm of consumer tech- full of “younger you” scores, motivational nudges, and colorful but clinically hollow dashboards. The other path embraces the complexity of human physiology, behaviour and healthcare: longer timelines, tougher evidence standards, and the humility to prioritize patient outcomes over product cycles.

It’s time to grow as an industry. The devices are powerful enough. The sensors are sensitive enough. The computational horsepower is here. The question is whether we will use them to create lasting health impact, or just better ways to admire ourselves.

Because in medicine, innovation without evidence is merely aspirational. And aspiration, no matter how sleek, isn’t enough to save lives.

Written by: Dr. Amir Hadid, Co-founder & CEO @ Sensifai Health | Adj. Prof., Faculty of Medical & Health Sciences, Tel Aviv University

Reviewed by: Dr. Emily McDonald Co-founder & CMO @ Sensifai Health | Assoc. Prof., McGill University Health Center and Dr. Dennis Jensen, Co-founder & CSO @ Sensifai Health | Assoc. Prof., McGill University

Thanks for reading DHI’s HealthTech Expert Column!

We hope you’ve learned as much as we did with this piece.

Stay tuned for next month’s Expert Column to keep gaining insights from various experts and stay ahead of the curve in digital health innovation!

Want to join the conversation? We’re always looking for new guest columnists to share their expertise with our audience.

Reach out if you’d like to be featured!